Q. How and where did it begin?

A. As a child, I spent endless Italian summers at the beach with my family in the mid-60s. I felt privileged in Italy; like Greece, the sea was always within reach. No coast was ever too far, and the summer climate was a true ally.

The appeal of sea bathing, even just to cool off, is perfectly natural. The Mediterranean, “Mare Nostrum“, especially in summer, is often very calm, and its long, gently sloping beaches create a wonderful outdoor playground for many families with children.

Additionally, certain family circumstances led me to develop a curious and mindful approach to swimming and water safety, which I consider inseparable. Coming from a large family and being the eldest among siblings and cousins, I often found myself working with parents and uncles to watch over the little ones at the beach. It was crucial to ensure they didn’t stray from the play area in the water without adult supervision,”…as the sea can be very dangerous!”

On the other hand, with obvious envy, I watched the same adults who scolded us having fun freely in the sea: my mother, an excellent swimmer, and especially my uncle Franco, capable of performing spectacular swims, particularly the butterfly stroke, with which he had won the regional championships a few years earlier.

As a child, life appeared straightforward: childhood meant not knowing how to swim, thus no swimming; adulthood meant mastering aquatic skills and enjoying the freedom to explore the ocean. Was it merely about waiting?

Resigned to the idea of a long wait, certain episodes made me question some things: on one hand, I observed children like me entering the water, even if very shallow, always under the watchful eyes of their parents and without the dreaded “floatie”; on the other hand, I couldn’t ignore that our father, an excellent rower who loved to take us out to sea on the “moscone,” never strayed far from the boat when he got wet. He claimed it was for safety reasons and didn’t want to leave us alone (undeniable reason), but the suspicion that he didn’t know how to swim, at least not like our mother and the “legendary” uncle, never left me…

Thanks to a fortunate coincidence, the solution to all my indecisions was already there, right before my eyes, on the same beach of the “Capri” Lido in Fregene, that we visited every day. It was a children’s pool, with deep blue tiles and rounded edges for added safety. Specifically designed to accommodate the little ones in complete tranquility, it featured two different depths: a section of 25-30 cm and another of 45-50 cm, connected by a full-width slide with a “gentle” slope.

I must admit that describing this place, which seemed truly magical to us, in the past tense is a mistake: that pool is still there, operational, unchanged, and perfectly preserved, for almost 60 years.

Many of the grandparents of the children now playing in that pool were my childhood companions in aquatic adventures. Francesco, the current owner of Lido Capri, was among them. Perhaps because of these memories, despite numerous renovations over the years, the children’s pool has remained always the same.

Whatever the reason, it was a true stroke of luck, because the unknown designer created an aquatic space as ideal as it is safe for the games and creative explorations typical of developmental age. The “shallow” part, which is little more than a pool, offers safety and invites even the youngest to enter the water – always accompanied by adults with water at their ankles or a little more – to become familiar with this new dimension. The “deep” part, on the other hand, is perfect for experimenting with the various and gradual transitions from the “terrestrial” vertical position to the horizontal swimming ones, with all their variations.

Among all my experiments from that period, certain moments have remained etched in my memory, especially one, which was fundamental: lying prone on the “shallow” bottom, I moved forward with my hands touching the seabed, moving towards deeper water. Using the momentum gained by “walking” with my arms and taking advantage of the gentle connecting slope, I was able to gradually detach from the rigid supports, initially sliding and then stopping in a surface float for a few seconds.

These small successes constantly fueled my desire to explore new aquatic adventures: diving, somersaults, twists, and seeking contact with the bottom. Although I wasn’t aware of it at the time, the theories of Jean Piaget, which I would study years later, proved to be incredibly effective!

Among friends, we constantly challenged each other, where competition was key. The focus was on quickly achieving goals rather than the methods to accomplish them. We counted the somersaults performed, ignoring how they were executed. To win, we devised all sorts of tricks and schemes.

Q. Did you have a guide who directed your choices within this lab-like pool? Maybe your mother, uncle, or a lifeguard? Or were you completely independent in making every decision?

A. As the oldest among siblings and cousins, the focus on water safety was primarily directed towards the younger ones. When I wasn’t enlisted by the “adults” to babysit the little ones, I could enjoy a certain freedom, which I took full advantage of. Naturally, everything happened under the watchful eye of a lifeguard, who intervened only if my safety or that of others was at risk. For instance, diving was absolutely forbidden for obvious reasons! Ultimately, I felt completely safe and, at the same time, free to imagine any situation.

It is essential to highlight how the fusion between security and creativity has always been an entirely instinctive and natural connection for me. During my childhood, I had the privilege of attending a Montessori elementary school, an educational environment where the freedom to experiment, albeit under careful guidance, was a cornerstone of learning.

I would have continued my aquatic activities calmly without any great expectations, until Antonella, my younger sister, driven more by her friendship with her best friend than by a genuine interest, asked our parents for permission to enroll in a simple “swimming course” (actually a “first aquatic orientation”) that Domenico, a young but highly respected instructor, was conducting right in that pool.

They granted her permission on the condition that I also enroll, at least to accompany her on the path from the play area to the small pool and back, without distracting the adults from supervising the younger siblings.

Domenico faced the challenge of managing two 6-year-old girls and a 8-year-old boy, each with distinct swimming abilities. The pool’s design was crucial: Antonella and Silvia started getting comfortable in the shallow end, while my best friend Stefano and I continued to develop our aquatic skills in the deeper water, staying just a few meters from the group.

Compared to my initial explorations alone, with Domenico, the experiences became something much more intriguing: instead of imposing predefined motor patterns on me, he preserved my freedom to explore the environment, allowing me to develop “rough” swimming techniques using my personal discoveries.

By the end of the summer of 1966, I was able to move freely in that small pool: I knew how to float, glide, dive, and perform propulsive movements underwater and on the surface, inventing new styles that we named with imaginative names like Turtle, Eel, Kitten, and others.

The exploration of these newfound freedoms in an enchanting world has transformed into a captivating children’s tale, published on fuorimag.it:

Alice in w-land (italian language)

Domenico seemed so pleased with my progress that he suggested my parents enroll me in a swimming class when we return to Rome after our summer vacation. The thought of continuing my personal explorations in the “magical aquatic world” thrilled me immensely…

…yet I never imagined that experiencing reality firsthand would be such an overwhelming surprise!

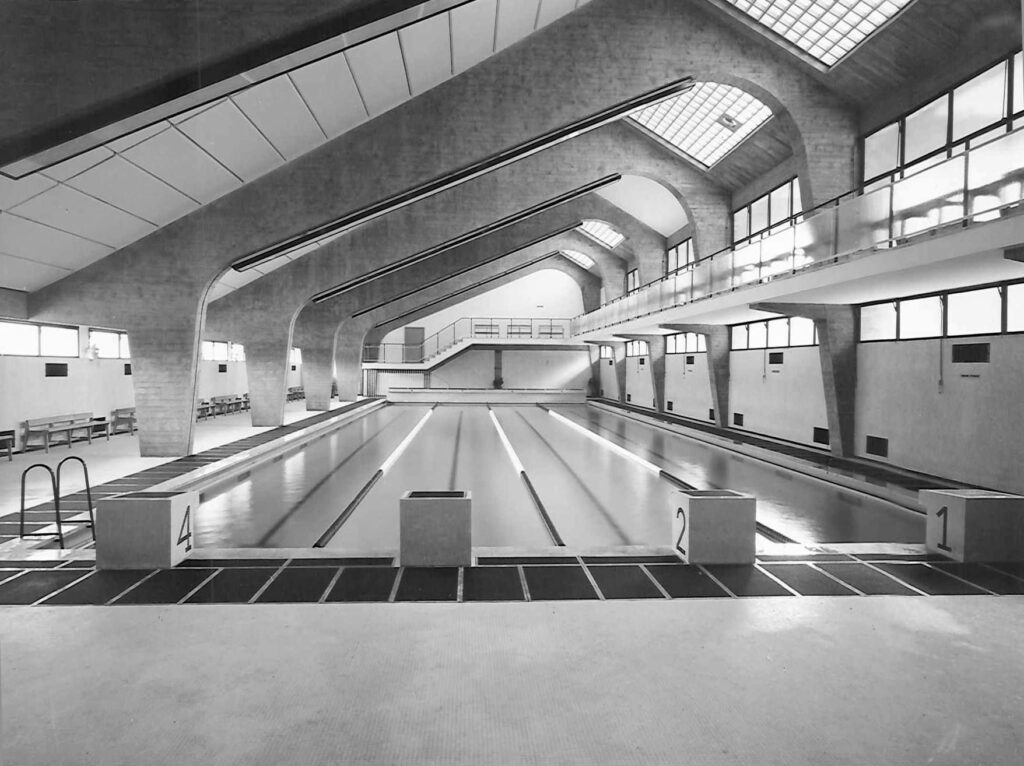

I prefer not to reveal the name of the sports club where I was enrolled, but it was likely the most prestigious during that time. The pools where beginner courses and training sessions took place were remarkable: the one at Stadio Flaminio, a masterpiece by Pier Luigi Nervi built for the 1960 Olympics, was cutting-edge and featured small stands for spectators…

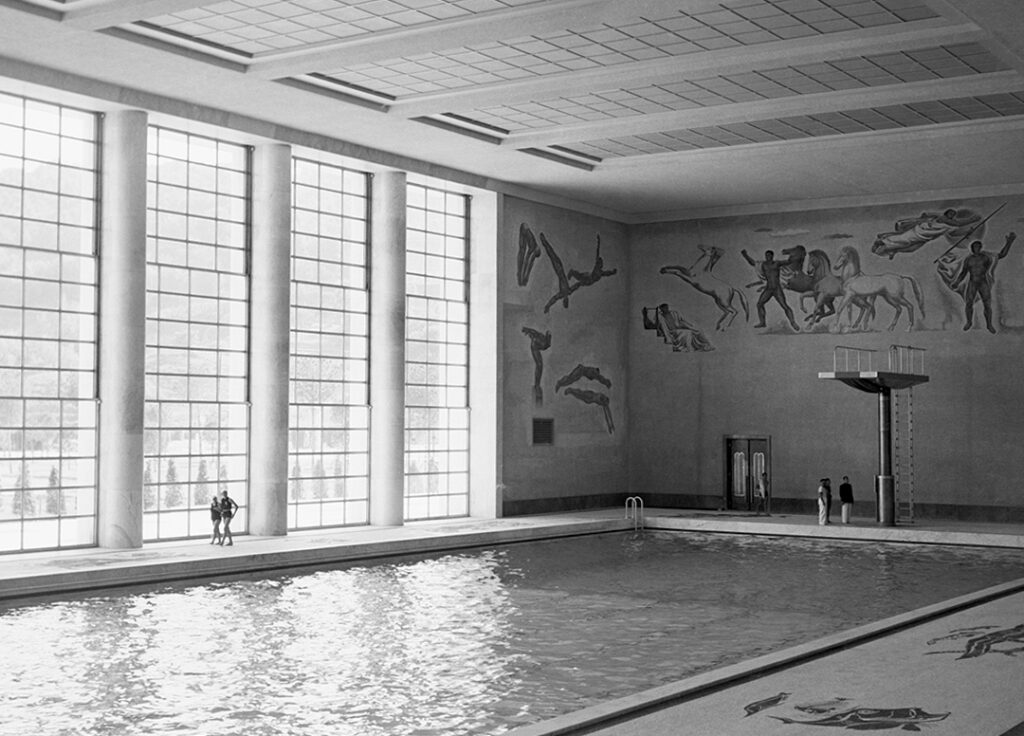

…and the “Piscina dei Mosaici” at the Foro Italico, a 50-meter marvel constructed in the 1930s, showcases breathtaking mosaics by Giulio Rosso that evoke a profound sense of awe.

Within these extraordinary architectural structures, behind the “swimming courses,” there were actually intense assembly lines, designed for the creation and meticulous selection of highly competitive athletes. The training offered, far from being a purely educational path, proved to be particularly strict and rigid, adopting a style similar to that of a paramilitary. The main goal was the perfect and flawless execution of predefined movements, strictly following the patterns imposed by the instructors.

The water in the pool was often extremely cold and heavily chlorinated, creating a truly unwelcoming environment. The instructors never stopped yelling, often insulting the recruits and accurately throwing foam kickboards at those who didn’t follow orders. The parents, comfortably seated in the stands, actively joined in the chants of reprimands directed at their children, supporting the atmosphere of strictness. Even the pre-swimming gymnastics turned out to be equally colorful, but with the difference that the objects thrown at recruits who failed to complete push-ups were hard rubber “superballs,” designed to bounce endlessly, which we were also required to promptly retrieve to rearm the slingshot instructor…

Q. They seem more like circles of hell rather than learning centers!

A. It may not have been Disneyland, but it was the swimming instruction style of that time, and it was accepted without question. Additionally, I attended the course with Bruno, a dear friend and classmate with whom I had developed a healthy sense of competition; I would never back down from the challenge!

Q. Was the transition from your elementary school’s creative/Montessori experiences and the Capri pool to the more rigorous environments of Flaminio and Foro Italico a bit too drastic?

For me, it marked the shift from the joy of discovering a new world to the duty of mastering the four standardized swimming styles. However, after reaching my goals and earning the notorious certificates, I promptly switched to track and field…

Q. Was it a completely negative experience, or is there something positive to salvage?

There were undeniably many positive aspects, particularly in the outcomes: the courses taught the four competitive swimming styles—backstroke, freestyle, breaststroke, and butterfly, known as “the four Olympic strokes.” Participants learned to follow rules, be punctual, refrain from complaining about workloads, embrace discipline, and challenge themselves alongside their peers. In relation to the stated goals, the courses were incredibly effective.

After a couple of years, I was perfectly capable of mastering “the four swims” and I was ready for the pre-competitive team; but that was certainly not “Swimming” as I envisioned it.

Q. What is the difference between “swimming” and “swims”?

This is a question as subtle as it is crucial, which was posed to me by Umberto Marini, a Master of Sport, during my exam to obtain the qualification of “Apprentice Instructor,” about ten years later.

I responded in a manner that was likely awkward linguistically; however, the notions of mathematical logic and set theory that I had just learned in high school came to my aid. The concept that “the four strokes constitute a subset of swimming” was deemed acceptable by the committee…at least until the next question, once again posed by Umberto, who pressed: “When you become an instructor, will you teach Swimming (with a capital S) or swimming techniques?”

(fine parte I)