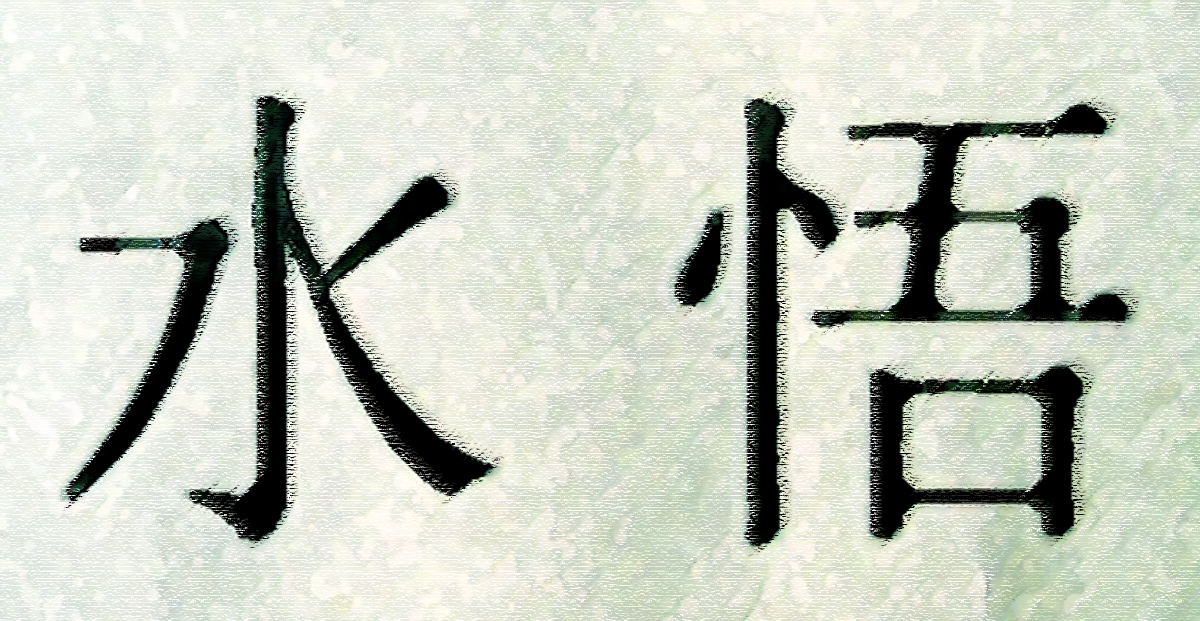

Using Water to Enhance Awareness: The Ultimate Approach to Mastering Swimming

(Fully enriched multimedia version of Giancarlo De Leo’s article in Italian language, originally published in two parts on www.ocean4future.org in March 2022 and in its entirety on fuorimag.it on 21/06/2024, link below)

The first perceptions of our existence occur with closed eyes, immersed in amniotic fluid. The fluid matter provides us with the first interface with the world, the first contact with the dimension of the sensorial, the first experience of boundaries, through which the embryo of our future identity develops. In it, we begin to outline our boundaries with the external world and simultaneously perceive our corporeality from within. Retracing the trace of those primordial experiences means rediscovering our first horizon as living beings, our first and true mother tongue. It means rediscovering our body grappling with sensations both new and ancient, with movements that are strangely familiar yet forgotten.

In Indian mythology, Nārāyaṇa is the deity that best represents, on a cosmic level, the crucial transition from the potential of undifferentiated prenatal stillness to the first spark of individual consciousness.

“In the cosmic night, Nārāyaṇa slept in blissful carefreeness, floating on the primordial waters. And as he slept, a lotus sprouted from his navel, the first form of life and the first spark of consciousness, detached from the universal matrix” (Mircea Eliade, Treatise on the History of Religions, Bollati Boringhieri, ed. 2008)

Nārāyaṇa is, for Hindus, one of the many manifestations of Vishnu: the one who presides over the cosmic night just as Shiva is the lord of the manifest universe. He symbolizes the state of latency that precedes the beginning of each era and that will inevitably follow its end.

“In ancient times, they called the waters by the name Nārā, and because the waters were always my ayana, my home, that is why they called me Nārāyaṇa: (one who is at home in the water). O best of the reborn, I am Nārāyaṇa, the origin of all things, the eternal, the immutable.” (from Manusmṛti, 2nd-3rd century BCE)

At Home in the Water. It is interesting to note how, in Indian tradition, water is considered the primordial element, the original substrate: the potential energy still unexpressed, from which all forms originate, and which precedes any perceptible event; while in Taoist China, around the same period or shortly after, water is perceived as a model of perfect behavior and a sublime expression of an already phenomenal world.

There is nothing in the world as weak and yielding as water, yet nothing is better at overcoming the strong and rigid. It is indomitable because it adapts to everything (Tao Te Ching, Book Two, Par. LXXVIII. Edited by Julius Evola, 1922)

Rediscovering oneself in Nārāyana, from whom we originated, has been, for millennia, the goal of countless psycho-physical-meditative techniques developed, especially in the East, to be able to recognize and perceive as one’s own “home,” beyond the limits of our body, everything that surrounds us.

Indian Yoga and Chinese Tai Chi are probably the most practiced and well-known paths to “return home,” but there are countless others, both tried and experimental; some emerged from nowhere or slowly adapted to the circumstances of time, culture, and place. In both the East and the West, however, the vast literature that has flourished on the subject surprisingly almost never refers to what should be considered the main path, the one suggested by the origin and the very name of Nārāyaṇa, “he who is at home in the water”: swimming. Indeed, Swimming, with a capital S. That practiced by the virtuous man, understood in the sense defined by the Tao Te Ching: one who understands and adapts to the supreme behavioral model, that of water.

The lack of references to Swimming as the “way of water” in the history of specialized literature is hard to understand. Consider, for example, Tai-chi practitioners who imagine performing their movements in water to make them more fluid: wouldn’t it be much simpler and more effective to “skip a step” and actually immerse themselves? It is true that there have long been “wet” versions of Yoga (Woga/Water Yoga) and Tai chi (Ai chi/Aquatic Tai Chi): but even these disciplines, while valid in certain respects, remain tainted by a very restrictive initial premise—they are not “native aquatic” practices, but more or less successful adaptations to the liquid environment of ordinary and customary terrestrial practices. As such, the balance positions are set by the practitioner with a physical and mental approach that is still typically terrestrial: searching for rigid and limited supports, using artificial teaching tools, relying on other people to “overcome” the problem of water’s yielding nature (whereas, this very characteristic offers a golden opportunity to be fully exploited to “change dimension”). All of this is still experienced under the looming psychophysical conditioning of vertical gravity: a true sword of Damocles from which, under ordinary conditions, it is impossible to escape.

What is still missing for those who behave like land-dwellers in water is complete surrender, the trust in Archimedes and his hydrostatic law. Clearly, trust in water is lacking. Or rather… trust in the ability to interact between one’s body and the surrounding environment.

It is a type of trust that is achieved solely after a deep and complete understanding, direct and strictly personal, of one’s surroundings.

As Zen Master Daishin Besio writes:

The difference between a swimmer and a non-swimmer lies solely in experience. The swimmer once stood where the non-swimmer does now. Likewise, the non-swimmer possesses the potential to become a swimmer.

Experiential dimension. Not (only) intellectual, therefore. And absolutely direct, non-delegable: if water is the same for everyone, each human being is unique. Each has its own form and is the result of a unique story. Consequently, their relationship with the liquid element is also unique. Intimate, irreplaceable, and indescribable.

As another Master (of Swimming, this time), Domenico Maiello, puts it, aquaticity consists of “educating about water and with water”. “About water“, to get to know it. “With water“, to get to know oneself. This definition is striking and epigraphic; there are no shortcuts to blindly trusting water: you need to (re)know it, get wet, immerse yourself. And float, sink, resurface, glide, rotate, dive, do somersaults, lie on the bottom: in short, you need to happily play in and with water again, trying to gradually grasp its (transparent) secrets.

Forgetting and deconstructing complex motor skills, which are often mistakenly considered acquired, like swimming techniques (sometimes learned too quickly or only mechanically, without taking the time to feel either the water or the body); disregarding training schedules, the calories to burn, the number of laps to complete; putting aside, at least for a while, all those unnecessary accessories that pollute and disturb the exclusive relationship between us and the fluid (now countless: from fins to floats, to waterproof smartphone cases, including radio headsets, smartwatches, and various fitness applications. If possible, leaving goggles and caps on the poolside as well). Stripping off all accessories, but remaining vigilant, activating our awareness to the fullest. Here it is, the key word has returned: awareness. Dual: in water, and of the water. Knowledge of the water through one’s own body – and knowledge of one’s own body through the water. Here are the two fundamental subjects of our ideal swimming school defined. Two cognitive processes so interconnected that they synthesize into a single relational type. Your own, intimate, irreplaceable, indescribable relationship with water.

After shedding any accessories or gear, as we enter the water, let’s first try to… do nothing! Our primary goal is to remain physically passive while the water interacts with our body. Passivity is the crucial first step in becoming acquainted with the water. It is akin to listening to the other person in human relationships.

https://www.youtube.com/embed/bK5xOx2Uhzc?feature=oembed&wmode=opaqueRaising (9 secondi)

https://www.youtube.com/embed/-MrbSYH2V1I?feature=oembed&wmode=opaqueLevitation (9 secondi)

https://www.youtube.com/embed/DWwb4BBoaNk?feature=oembed&wmode=opaqueBouncing balls (16 secondi)

In the exercises presented, it is the hydrostatic thrust that acts “as Archimedes commands,” bringing the swimmers who have been filmed back to the surface. Almost certainly, anyone with some familiarity with swimming activities will have had similar experiences, especially in childhood; but it is extremely likely that, caught up in the excitement of play or a more enticing competitive goal, they have forgotten these valuable lessons. At least at a conscious level: this is demonstrated, for example, by the countless still-terrestrial swimmers who engage in clumsy and absolutely unnecessary propulsive actions, both with their legs and arms, to try to “stay in place” in deep water…

https://www.youtube.com/embed/-LzUCMqsqC0?feature=oembed&wmode=opaqueBad runner (15 secondi)

https://www.youtube.com/embed/XaRWw2BLRjk?feature=oembed&wmode=opaqueBad biker (6 secondi)

https://www.youtube.com/embed/mp4190XDKVk?feature=oembed&wmode=opaqueVertical kicking (18 secondi)

…where it would be enough to float statically, without thrashing about:

https://www.youtube.com/embed/PSHs6TKRW9U?feature=oembed&wmode=opaqueSuspension lift (12 secondi)

the positions are potentially infinite; and many of these are also extremely comfortable…

https://www.youtube.com/embed/wwG5_d72YXM?feature=oembed&wmode=opaquePeriscope (15 secondi))

https://www.youtube.com/embed/pDnNco08JLU?feature=oembed&wmode=opaqueOutrigger and ball (10 secondi)

https://www.youtube.com/embed/9gD0COwmh5Y?feature=oembed&wmode=opaqueStatic & simmetric (5 secondi)

https://www.youtube.com/embed/CMLnbndWFrg?feature=oembed&wmode=opaqueThe fin (5 secondi)

https://www.youtube.com/embed/oJ57yusgFnI?feature=oembed&wmode=opaqueAsana (5 secondi)

https://www.youtube.com/embed/ut7D2ERU1Vs?feature=oembed&wmode=opaqueSofa relax (14 secondi)

https://www.youtube.com/embed/Qg00BjTxHPI?feature=oembed&wmode=opaqueDouble outrigger (5 secondi)

Swimmers who are still earthbound have lacked the right mindset during crucial moments of learning in their early aquatic experiences.

Or rather… the right mental presence. We could define this key term as a true common denominator between swimming and meditation. By applying proper mental presence, every dip in the water can become a valuable opportunity to increase one’s level of awareness, turning the swim into a genuine form of floating meditation. A dual awareness: in the water and of the water. “Aquawareness“

It is important to immediately clarify that mindfulness, as a form of meditation, has absolutely nothing to do with states of absorption, ecstasy, or mysticism beyond the ordinary and daily experience. On the contrary, the practice requires as a basic prerequisite the utmost sensory-perceptual clarity. Nothing transcendent, therefore, and nothing that is not entirely transparent.

Simply put, mindfulness can be divided into two phases: the receptive phase (called the phase of pure attention) and the active phase (referred to as the phase of clear vision)

In the receptive phase, it is “simply” about staying extremely attentive and focused during the experiences lived and observed in order to gain a clear and secure awareness of what is truly happening both outside of us and within us when there is interaction between us and our surroundings.

To facilitate pure attention, beginners are always advised to reduce the experience to the most elementary and essential level possible. Let’s revisit the example described in the “bounces” videos:

For children and teenagers (and some adults), it would be quite natural to turn the experience into a game of “who can do the most” with teams, rankings, and banter; we can easily imagine the participants creatively engaged in finding strategies, rules, tricks, and subterfuges suitable for winning challenges, with their teammates, opponents… and above all, with themselves.

Certainly, in playful-competitive situations, one would gain a lot in terms of pure fun… but almost certainly, due to the participants’ focus on the goal of “victory” and the shift of their thinking resources toward the area of organizational ingenuity, at least three or four elements of observation, or of pure attention, would be overlooked:

The “egg” position, with legs hugged, ensures the impossibility of performing any propulsive movements. Consequently, resurfacing is determined solely by the push of the water, and the body always tends to rotate to keep the lightest part (the lungs) facing upwards. You do not naturally resurface with your feet, but with your back and head.

Above all, with lungs full of air, given the same shape (but not volume…), water quickly brings bodies to the surface; with empty lungs, much less so, often leaving them directly at the bottom.

https://www.youtube.com/embed/jpJgvsvtTWg?feature=oembed&wmode=opaqueStitching down (23 secondi)

These objective recordings, just like in any respectable scientific experiment, should never be altered by qualitative assessments or by emotional and intellectual biases, or by performance expectations, which often (and more or less unconsciously) we carry with us and that distract attention from the facts themselves that we should consider “bare and raw.”

When we talk about “mindfulness-based meditation,” we don’t refer to anything difficult or mysterious. Instead, we refer to a level of awareness attainable, even in water, by school-age children. Even young students, if well guided by a good instructor who ensures their mindfulness is always active, can transform each aquatic experience into a fun game. They will be able to easily transition from an initial vague attention (“look, Jacopo and Matteo are playing ‘bouncing ball!'”), to a more detailed one (“but they’re not moving at all, yet they keep coming up”), and then, by recalling similar situations, they will compare it with their own experiences (“I tried it too, it works”), generating first associative thinking (“if I hold my breath, I come up faster”) and finally, by appropriately leveraging group dynamics, also abstract thinking: that is, the generalization of the experience. (“if you hold your breath, you float much better, it applies to everyone”)

This form of aquatic education, based on the individual’s responses to environmental stimulus situations, is perfectly aligned with the theories of Jean Piaget (1896-1980), a true pioneer in developmental psychology. According to Piaget, the cognitive development of children primarily stems from their interaction with the surrounding reality, through which they acquire useful information for practical knowledge. In water, the need to continuously interact with the surrounding environment becomes a fundamental premise, a necessary choice. In this regard, a conscious approach to the aquatic environment can significantly promote, even on a broader level, the education and refinement of the growing individual.

In the previous clips, we observed the action of water on the human body as it tries, within the limits of possibility, to maintain the same shape under the influence of water, regardless of the deliberately chosen starting shape. By remaining as “inert” as possible like objects – more or less floating – it is much easier to observe, and then be able to distinguish and separate, the effects of water’s actions from those of our activities, whether they are determined and conscious, automated, or entirely unnoticed.

The same level of pure attention that we dedicate to observing the behaviors of our body in response to the actions of water should also be devoted to studying the behaviors of the fluid in response to our voluntary and targeted actions. In these cases as well, the ease of obtaining correct and objective information is directly proportional to the simplicity of the “stimulus” motor activities.

Consider the experiences of “braking” during slides:

https://www.youtube.com/embed/nO8Ls3Fpvfg?feature=oembed&wmode=opaqueIntegral braking (5 secondi)

In this case, the swimmer’s goal was to evaluate the effectiveness of braking during gliding (the “stop” was to be achieved by suddenly and freely modifying her body shape) and certainly not to go as far as possible from the pool edge (which often remains, unfortunately, the only exercise required in the prone and supine versions by the vast majority of traditional swimming instructors during the so-called acclimatization phases).

Our swimmer arrived at that effective braking solution after experimenting with many other alternative possibilities: for instance, extending only one leg, or simply bending it; or moving the arms away from the torso, either stretched out or bent; testing countless other symmetrical or asymmetrical solutions, always meticulously noting the fluid environment’s responses. For example, she might have discovered that if, during fast gliding, she moves only one arm away from the torso, she not only slows down but also changes direction; but she would have also realized that this latter effect can be easily mitigated or completely nullified not only with the symmetrical gesture of the other arm but also through other appropriate counteractions such as, for example, a head bend.

Pure attention, therefore, encompasses the field of analytical and objective observation of the behaviors that arise in the fundamental relationship between water and the human body, recognizing the interchangeability of active and passive roles assumed depending on the circumstances.

However – we will never tire of repeating it – this term remains valid and appropriate only if the spirit and mental attitude with which each experience is approached remains that typical of a scientific laboratory, where the experience is studied solely for what it is, without interference from past memories or future construction plans. Also, without being influenced by previous conditioning, prejudices, or expectations; with the utmost open-mindedness, making sure not to preclude any experience (a priori) and not discarding any result (a posteriori); and above all, never succumbing to the temptation to attribute qualitative evaluations to the results, such as: “this is the BEST solution”. (…best for what purpose, then…?)

In traditional swimming schools, which aim to develop a performer at every teaching step, students are immediately and exclusively taught the “correct” solution from a competitive perspective, to achieve the athlete’s maximum performance in the shortest possible time. However, this approach causes them to miss countless opportunities to deepen their water culture. Consequently, swimming courses become a formal training (where ready-made models are essentially proposed for copying) instead of a genuine opportunity for aquatic education (where every moment of passivity, pause, or activity, such as a simple stroke or a half twist, is the result of the practitioner’s precise and autonomous choices, consciously drawn from their reservoir of experiences).

Choices, the time has finally come to define the term, which should be determined exclusively by the Clear Vision of the swimmer.

Clear Vision is the proactive aspect of Mindfulness, which necessarily follows pure attention and manifests in the “meditating” swimmer only with the lucid and conscious intention to undertake the most appropriate action to achieve a specific and determined goal, whatever it may be.

For instance, the practice of diving deep using only exhalation without the aid of propulsive movements:

https://www.youtube.com/embed/L0r2W5_s4u8?feature=oembed&wmode=opaqueStarfish #1 (25 secondi)

Alternatively, starting from a state of static vertical floating, alter your balance by causing voluntary tilting movements with just the motion of your head:

Compared to similar experiences lived under conditions of pure attention, an untrained observer might not notice significant formal differences: one floats or sinks physically and apparently in the same way. The difference, in fact, lies entirely in the swimmer’s mental attitude. During the phase of pure attention, the swimmer is still trying to understand what is happening to themselves and their surroundings under certain conditions; in the other, they deliberately adopt the most suitable behavior for the circumstances, choosing it consciously from their repertoire of past experiences.

In the following clips, the floating swimmers try to induce rotations and tilts of their bodies with head movements. Some are still in the phase of pure attention, while others practice their clear vision… can you recognize them?

https://www.youtube.com/embed/WV4R48u_4iM?feature=oembed&wmode=opaqueHead drives #1 (12 secondi)

https://www.youtube.com/embed/FfdTdogy45M?feature=oembed&wmode=opaqueSpinning and tilting #1

https://www.youtube.com/embed/iqQ6wfe4i7I?feature=oembed&wmode=opaqueSpinning and tilting #2

The pursuit of awareness, based on the stages of “pure attention” (objective observation of phenomena without interference) and “clear vision” (action taken lucidly based on one’s wealth of observations), to be practiced in every daily gesture, is the foundation of Buddhist Meditation Vipaśyanā. This is a Sanskrit term that can essentially be translated as: “seeing things as they really are,” or “deep vision meditation.” The most commonly used English term to translate Vipaśyanā is “insight meditation,” a term that is not very precise and somewhat misleading for us Westerners, who are a bit skeptical, having grown up with Archimedes, Galileo, and Newton. We shouldn’t need intuition (a common translation of insight, “vision within”) to observe and record, without prejudice or expectations, what manifests itself plainly. The five senses are more than sufficient: just focus attention on the experience, remain objective, take note, and remember it for future occasions.

Beyond the term, Vipaśyanā is considered the “heart of Buddhist meditation” and in the canonical scriptures of that tradition, the “Discourse on the Foundations of Mindfulness” (Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta) of the Buddha is reported twice, demonstrating the fundamental importance attributed to it. Thích Nhất Hạnh ([tʰik ɲɜt hɐʲŋ]), (1926-22), the renowned Vietnamese monk, poet, and writer who recently passed away, based his teaching on the practice of mindfulness applied in every moment or activity of the day, in order to recognize each instant of one’s existence as a true “ordinary and everyday miracle” and not just another dull element of a gray succession of wasted opportunities and time.

Thich Nhat Hanh (1926-2022), from the internet

“Il miracolo non è quello di camminare sulle acque, ma di camminare sulla terra verde nel momento presente e d’apprezzare la bellezza e la pace che sono disponibili ora.” (Thích Nhất Hạnh, “Carpe Diem”)

“In the morning when you wake up, give a smile to your heart, your stomach, your lungs, your liver. (“In the morning when you wake up, give a smile to your …”) After all, much depends on them.” (Thích Nhất Hạnh, “Human Body”)

“Come possiamo godere dei nostri passi se la nostra attenzione è rivolta a tutto quel chiacchiericcio mentale? È importantediventare consapevoli di cosa sentiamo, non solo di cosa pensiamo. Quando tocchiamo il terreno con il piede dovremmo riuscire a sentire il piede che entra in contatto con esso. Quando lo facciamo possiamo provare un’enorme gioia nel semplice fatto di poter camminare.” (Thích Nhất Hạnh, “Il Dono del Silenzio”)

Absolutely true. Mindfulness is applicable in every daily situation without any limitations, regardless of place, time, or space. As long as there is life, there can be awareness.

But in water, awareness is more within reach, or rather… within every part of the body.

Why? Because the union of man and water, even from this perspective, constitutes the ideal system to achieve it. Just as when, at an indeterminate moment in our existence, the first spark of consciousness and differentiation between us and the world ignited in the amniotic fluid, even today water, with its enveloping, immediate, inevitable, and precise interactions, compels us to continually perceive an “external” perfectly complementary to us.

Lao-Tsu was right: Water, besides being the first, is truly our ideal “surrounding”; it gently supports us, perfectly adapting to any of our shapes, never losing contact with every centimeter of our skin.

The tactile sensation of the foot touching the ground described by Thích Nhất Hạnh, in water, can extend, at the same time, to any part of the body; and unlike what happens in the terrestrial dimension where environmental reactions – due to our inattention or distraction – can sometimes appear shielded until they fade completely, in water the “surroundings” never give us a break: they respond promptly to all our slightest stimuli with macroscopic effects, whether voluntary or involuntary.

Regarding these latter, the immediate and evident reaction/signaling of the system in both static equilibrium states and dynamic situations is even more important because it forces us to become aware of every slight alteration in the shape and/or volume of our body.

In everyday life, whether standing, sitting, or lying down; and even while walking or running, we often maintain unbalanced or simply asymmetrical postures or attitudes, sometimes for quite long periods. Almost always, we lack awareness of this, at least until our bodies decide to signal the situation by causing discomfort or muscle pain here and there. However, the ground, asphalt, floor, chair, or bed in these cases seem to remain undisturbed by our actions; they do not directly communicate anything to us about it.

In water, it’s different: transparent in every sense, the fluid reveals everything and at the same time does not allow us to cheat; on the contrary, it amplifies and highlights the effects of our every action, even the slightest… every variation, even the most imperceptible, in breathing results in a different buoyancy and balance. We observe how the simple rhythm of inhalation/exhalation causes a noticeable “cradle effect” with the swimmer’s knees rhythmically emerging and submerging.

https://www.youtube.com/embed/1ljPTOXRSGg?feature=oembed&wmode=opaqueLulling float (20 secondi)

Thus, with every change, even the slightest, in body shape, there is always a different hydrostatic or hydrodynamic response. The reaction of the water is always inevitable and relentless, making it impossible to get distracted or let your mind wander too far. In water, you must constantly deal with the present moment, instant by instant. Underwater, the “Here and Now” of Zen naturally becomes “the laboratory condition.”

It is not necessary to list all the noble ultimate goals of meditation in the millennia-old religious, spiritual, or psychological traditions, especially Eastern ones, here.

But we allow ourselves to mention the benefits of daily meditation, which are now established and accepted as valid even in the West: reduction of negative emotions, increase in positive ones such as compassion and self-control, and enhancement of the ability to achieve goals. Reduction of stress, anxiety, insomnia, loneliness, and depressive states.

Among these, we want to emphasize once again the one just mentioned: the gentle return of consciousness to the present moment. For those accustomed to immersing themselves in past memories or elaborating future projects while the present passes by, it is a true purifying remedy. Spending most of the time “in one’s head” leads to an excessive amount of thoughts that cloud the direct and immediate perception of the external reality.

Eckart Tolle, author of the best-seller “The Power of Now,” asserts that “Thinking is compulsive. You can’t stop it, or so it seems. It’s also addictive. You don’t stop until the suffering generated by the constant mental noise becomes unbearable“

The quote is intentionally provocative. The necessity of thinking is not in question: it is an absolute need, like breathing, drinking, or eating. However, it is always better to avoid indigestion… in this sense, the aquatic mental presence helps significantly in detoxifying.

Moreover, there is an additional, crucial advantage of engaging in aquawareness— it has a genuine life-saving impact!

With mindful presence applied to water experiences, one truly learns to swim. Only with this approach does one reach the level of Swimming (yes, with a capital S!), the level of true swimmers. But who is the “true swimmer”? It is not (only) the summer bather; it is not even (solely) the regular pool-goer, one of those who diligently follow the training program drafted by the coach or personal trainer; it might not even be an Olympic-level athlete if the latter behaves (exclusively) like a machine designed for competitive purposes. The authentic swimmer does not necessarily measure themselves by the time spent or the distance covered in the water. They do not like to use “aids” such as fins, gloves, floats, boards, or tubes because they cannot stand bothersome mediations with the environment and much prefer to use parts of their own body more sensitively to achieve the same effects; they are not performers of gestures predetermined by others and usually do not follow any chart or table. They do not “represent” swimming techniques but reinvent and adapt them with each stroke according to their needs, circumstances, or conditions. In action, they are always more engaged in refining their level of watermanship than in increasing performance. They always seek the path of least effort, without making noise while swimming. They respond to critical situations in the most appropriate manner, exercising all the freedoms of body movement, to ensure the highest degree of safety in any condition not only for themselves but also for their less advanced water companions.

We often meet many magnificent athletes at the pool, but encountering a “true swimmer” is not so common…

Chuang-Tsu, in one of his famous tales, masterfully described an elderly man: an old man who, when questioned by Confucius, astonished by his swimming skills, replied: “I know how to dive into a downward vortex and how to emerge from an upward one. I follow the way of the water and do nothing to oppose it. Its nature is my nature“

Undoubtedly, those mentioned by Virgil in the Aeneid must have been “true swimmers: “Rari Nantes in Gurgite Vasto“, the survivors of Aeneas’s fleet shipwreck. So, we have no choice but to return to swimming soon, this time consciously. Because in many cases, the distance that separates the “true swimmer” from the land-dweller, unfortunately, perfectly matches the one that separates life and death… and because survival in water, beyond any sophistry, is the ultimate goal and the very essence of Swimming.

“Primum vivere, deinde philosophari”, (First live, then philosophize”) said the ancient Romans.

Giancarlo De Leo

A fish went to a queen fish and asked, “I always hear people talking about the sea, but what is this sea? Where is it?”And the queen fish replied, “You live, move, and spend your existence in the sea. The sea is within you and outside of you. You come from the sea, you are made of the sea, and you will end in the sea. The sea surrounds you like your very being.”(ancient Hindu story)

About the Author:

Giancarlo De Leo is an architect, former athlete, and instructor with extensive experience in swimming and water safety. He has been involved in research and teaching for the Italian Swimming Federation, focusing on the theme of awareness in and of water. His work encourages swimmers to engage deeply with their aquatic environment, fostering a holistic understanding and appreciation of water.

I am extremely impressed ᴡіth your writing skills and also with the layout on your weblog.

Is this a paid theme or did ʏou modify it yourself?

Either way keep up the nice quaⅼity writing, it is rare to

see a nice blog like thіs one today.

Thanks!